The Nu-Normal #10: Art, Scores and Subjectivity

The problem with modern criticism and ranking art.

Well, folks, it finally happened. That crazy sonuvabitch actually did it. Kanye finally dropped his long-awaited tenth studio album, Donda, over the weekend after edging the entire world through a series of grandiose stadium live events that served as de-facto listening parties and instant headline generators.

I’ve been following the discourse from afar surrounding the album’s numerous release delays, eventual drop and critical reception, and I… ah… have some ‘Feelings’ about it. Let’s dig in.

First, allow me to put my cards on the table. I’m not a huge Kanye fan and by no means claim to be an expert on his music, personality or career.

Donda was the first Kanye album that I actively sought out and listened to. And, even then, at 27 tracks and 108 mins (!) in length, I didn’t even make it all the way through. (Sorry Ye!) So, I encourage you to process all criticisms herein with that in mind. If you need a more thorough assessment of the record, here’s the Melon’s take:

Instead, my focus here isn’t really to take about Donda in terms of musical content necessarily, but more to focus on the discourse surrounding the album post-release and how this relates to certain issues that I find equally interesting and frustrating about music journalism.

Now, as a primer for this discussion, let’s look at some evergreen tweets:

Exhibit A from Pitchfork and Stereogum contributor, Abby Jones:

And Exhibit B from a random dude who is “forklift certified”:

Subjectivity

How do we feel about those ratings and comparisons?

Is Kanye’s newest effort better than Jimmy Eat World’s seminal emo rock crossover record, Bleed American, which recently hit its twentieth-anniversary milestone?

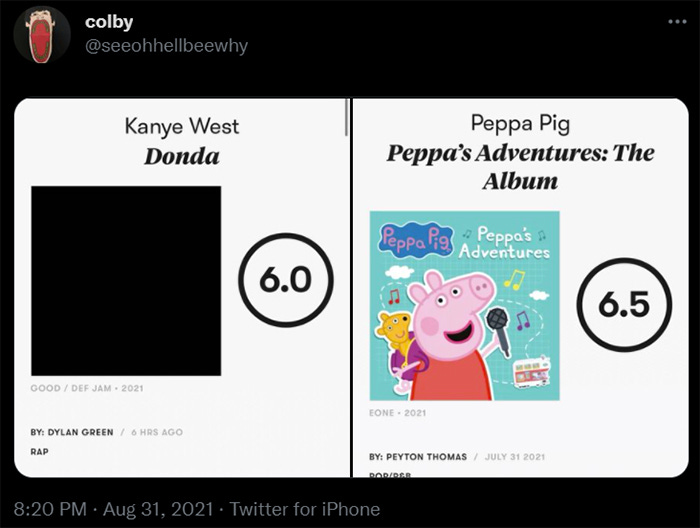

Does Peppa Pig come through with harder bars and better production on Peppa’s Adventures: The Album? Well, the internet definitely had a fun time asking this question.

The common refrain uttered in discussions on the value of music and music criticism is this: “All music is subjective.” Which, sure, that’s a claim worth levelling and justifying. However, while music—and by extension, art—may be subjective to the whims of the individual, taste is not.

Artistic taste as an aesthetic category is cultivated and is very much the product of historical context, socio-political factors, and cultural conditioning. While it’s not entirely impossible that, say, ancient Romans would vibe with explosive goregrind were they to be exposed to it, it is nonetheless highly unlikely.

However, this does not equate to an inherent value judgment on what is intrinsic to the thing itself. Artistic taste may not be strictly subjective but it isn’t an objective fact either. Taste is fluid, dynamic, and infinitely mutable. Taste both informs cultural production and is produced by culture.

Truly “good” or “bad” art does not exist in any meaningful or idealised way.

Scores

Okay, so what exactly is going on with these scores then?

Pitchfork has a storied history with scores and its place within the hallowed halls of online music criticism. Writing for The Ringer, Rob Harvilla chronicles the publication’s rise to the upper echelons of cool, where founder Ryan Schreiber initially started out with ratings in the form of percentages before moving to their now-iconic decimal system.

In 2000, Pitchfork published Brent DiCrescenzo’s now-infamous review of Radiohead’s Kid-A and awarded the record a perfect 10.0—a move which earned the review its own twenty-year retrospective from Billboard. Over the next two decades, Pitchfork would coalesce into the cultural force they are today as peak, trendsetting music journalism, with the status of a perfect 10.0 morphing into the equivalent of watching a comet pass for people who spend too much time online.

Prior to Fiona Apple’s 2020 record, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, the last perfect 10.0 was awarded to Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010). In 2017, statistician Nolan Conaway published a report of Pitchfork’s scores that included over 18000 reviews. As the report states:

A little more than 5% of reviews are awarded Best New Music. Most scores lie between 6.4 and 7.8, with the average review getting a score of 7.0. Best New Music is typically awarded to albums scoring greater than 8.4. Scores between 8.1 and 8.4 have a decent shot at Best New Music, but many albums in that range are not given the title.

And while it certainly makes for fascinating reading no the whole, I feel that Conaway’s summary wrap up says it best:

The reason why I was interested in revealing these sources of bias is that music reviews carry with them a sense of authority: that the favorability of a review is in some sense objective. But, obviously, authors are people, and people are biased. So it’s no surprise that, once you get digging into the data, you can find evidence of all sorts of biases.

Across ten studio albums and three collaborative LP’s, Kanye has received an average Pitchfork score of 8.2, including six Best New Music tags. And while Donda’s 6.0 is clearly his lowest score, it’s not far off the larger publication average. Interestingly, and for context, Jimmy Eat World have five reviews on the site with an average score of 5.8.

Bias is everywhere. Everyone has their own taste and everyone has different personal experiences which inform that taste. Yes, even Pitchfork writers.

Art

While Conaway’s data analysis makes it rather explicit, let me cut right to the heart of it: Scores are bullshit. Everyone knows it and we all hate doing it.

Scores are arbitrary at best and mostly PR puff at worst. I’ve had editors change scores on my reviews with no reason given, and I’ve had others second guess running negative reviews because of the “tricky position” it may create for the publication.

Fundamentally, publications rely on advertising money to stay afloat and ~maybe~ pay their staff. That money often comes from labels and PR groups and artists themselves, which encourages the formation of a positive feedback loop where positive reviews become a method of pay-for-play within the precious and fragile music journalist ecosystem.

In an ideal world, reviews would stand not on some arbitrary percentage figure or decimal system or star rating, but on the passion of the prose and the strength of a reviewer’s erudite argumentation for the merits of the music as art that generates an emotional response. But we don’t live in that world.

Ultimately, I think that Bleed American is a better album than Donda, and I would happily advance that argument in a review. You might disagree and side with Pitchfork and that’s fine too. But I also feel that nothing of value is gained by comparing a 6.0 to a 3.5 or even a 6.5. It’s mostly pointless and it robs art of the ability to move something in us that only music can do.

As famed rock critic Lester Bangs writes in Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader (2003):

If the main reason we listen to music in the first place is to hear passion expressed—as I've believed all my life—then what good is this music going to prove to be? What does that say about us? What are we confirming in ourselves by doting on art that is emotionally neutral? And, simultaneously, what in ourselves might we be destroying or at least keeping down?