The Nu-Normal #16: I Fetishize, Therefore I Am

Meditations on trends, virality, and the parasocial spectacle.

There’s a lot going on in this week’s column. I take a look at a recent controversy and trend surrounding a number of high-profile musicians receiving pressure from various record labels to generate (read: fake) ‘viral’ moments on TikTok.

This discussion then led me to consider the nature of virality itself, how it functions in our current hyper-mediated culture of ephemeral experiences and commodity fetishism, and the impact of parasocial relationships on our chronically online society of the spectacle. (Also, here’s your content warning for dangerous levels of over-philosophizing.)

So, if that sounds like fun and/or interesting to you, then, by all means, read on.

TikTok and Toxic Trends

Back in May, American singer-songwriter Halsey shared a 30-second video on her TikTok profile that managed to gain eight million views in under 24 hours.

The fallout from the video then kicked off a furious discussion among her devoted fans, peripheral TikTok users, and music industry insiders:

For those of you who can’t be bothered watching Halsey’s digital screed, the displayed text reads as below:

“Basically I have a song that I love that I wanna release ASAP but my record label won’t let me. I’ve been in this industry for 8 years and I’ve sold over 165 million records. And my record company is saying that I can’t release it unless they can fake a viral moment on TikTok. Everything is marketing. And they are doing this to basically every artist these days. I just wanna release music, man. And I deserve better tbh. I’m tired.”

Suffice to say, responses were mixed and interesting. Ride or die Halsey fans were of course there with comments of support and mutual frustration for their songbird queen. Other fans, however, noted that Halsey’s position was inherently one of privilege: her platform as a celebrity and established artist affords her the ability to complain about label drama—real, manufactured, or otherwise—in this way. The contrast is that many artists continue to struggle in obscurity and digital darkness, creating art that will never reach an audience even closely approximating Halsey’s arguably substantial reach.

Others also noted how Halsey’s position reflects a larger disturbing trend among the upper echelons of the music industry. As D. Bondy Valdovinos Kaye writes in The Conversation, there’s a circularity to this whole exercise that exposes the pernicious aspect of corporations chasing trends in popular culture:

“Whether staged or not, the fact that these two videos went viral so quickly shows people are willing to believe a major artist would be so frustrated with their label forcing them to ‘do TikTok’ that they decided to expose their label on TikTok.

Like MTV or top 40 hits radio stations before it, TikTok is where popular music lives right now. Labels understand that. To them, the allure of TikTok is that musical content can go viral quickly, offering the potential to save millions on other types of marketing campaigns.”

It’s all too clear that the calculus being performed here is simply one of capitalist imperative and sunk cost efficiency, where music is viewed not as the realm of art and creative expression, but as a commodity to be marketed and sold at a profit. And to be clear, this is not a new phenomenon—it’s merely changing form.

Ultimately, however, this type of controversy centres around questions of authenticity. Clearly, an artist faking a viral moment is inherently authentic. But what about going viral on TikTok… for talking about the pressure to go viral on TikTok? At what point are interactions between an artist, their label, and their fans an authentic representation of their relationship to their art? Is it just endlessly curated “moments” and stitched video chains all the way down? Nobody knows. Here’s Kaye once more:

“Fake or genuine, Halsey’s video shows fans and artists are willing to have a conversation about how labels exert influence over artists when it comes to marketing, the nature of obligations artists contractually owe to their labels and the power artists wield to push back against labels if they feel they are being treated unfairly.

Viral rants on TikTok are not going to become the new normal for selling songs, just like video never actually killed the radio star. Label executives watching this unfold are likely more nervous about their own artists publicly airing grievances online than they are excited about a new trend in viral music marketing.

Regardless, as long as audiences continue discovering new music on TikTok, labels will continue searching for new ways to promote their music to the top of the feed. The core job of the artist – making music – remains the same. Only now the video needs to go viral.”

Vicarious Virality

Okay, but if this is our new status quo for success in the music industry, what exactly is virality anyway?

The idea of ‘viral media’ can be traced back to the 1980s and the advent of personal computing and burgeoning Internet infrastructure. Through news reporting, the concept of the ‘computer virus’—nefarious code or data that could penetrate native computer systems for the dual purpose of corruption and self-replication—entered the sphere of popular culture, taking its name from biology and the process of virus propagation observed in nature.

In conceiving a theory of viral modernity, Michael A. Peters notes that the concept of virality applies to expressions of thought, information, and data and the processes of circulation and distribution offered by mass distribution mechanisms like social media:

“All information that is easily shareable and websites that promote electronic sharing and exchange through decentralising platforms enable users to flick on or spread memes, leading to what many now see as an aspect of network culture and the cultural politics associated with it, which often means that content users become creators who can use or modify content.

Network culture then is a recent reflection of the last few decades of internet use brought about by increasing interconnectivities on open platforms that increase the speed, velocity and scope of information, often also personalising messages and spreading hype, gossip and bullying comments that disrupt peer cultures.

[...] In social digital networks, viral media does not discriminate between information and knowledge: it can generate and circulate information irrespective of its truth value. It is an ideal medium for hype, exaggeration, falsehood, lies and gossip that are characteristic of the age of post-truth.”

What this understanding illustrates is the epistemological and phenomenological gap between the qualifying criteria of virality as obscured by the shadowy nature of Big Tech and their algorithmic distribution models (i.e. TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, etc.) and the desired outcome of end-users (i.e. music fans, record labels, etc.) as willing consumptive subjects, each with differing (sometimes drastically so) motives.

All of this to say, then, that no one really knows how ‘viral moments’ truly happen, because the entire process is obfuscated and hidden behind layers of capitalist consumption, engagement metrics, and the pervasive yet entirely fickle attitudes of popular culture. One pertinent example is the resurgence in popularity of “Running Up That Hill (Make a Deal with God),” the 1985 single by Kate Bush:

In a recent piece for Variety, Jazz Tangcay describes the many steps—the intricate process of song selection, artist approval, and securing publishing rights—necessary for the single to be included as a major plot device in season four of Netflix’s Stranger Things.

While all of those details are fascinating in themselves, I mention them here because none of that work necessarily guaranteed the viral success of a near-forty-year-old song in 2022. It was simply picked up for inclusion in a streaming show, audience members resonated with its symbolism, and then fed the track through mechanisms like TikTok, Spotify, and Twitter to viral success. Broadly conceived, this is less of a marketing campaign than pure luck and happenstance.

And if this is the case for an icon like Kate Bush and a song that’s been publically available for decades, how does this process factor in for emerging artists or even celebrities like Halsey? Is this really how we want musicians to gauge their success and artistic fulfilment? By somehow magically cracking the digital code of virality again and again, in perpetuity, as the algorithmic seasons change without any discernible rhyme or reason?

The Parasocial Spectacle

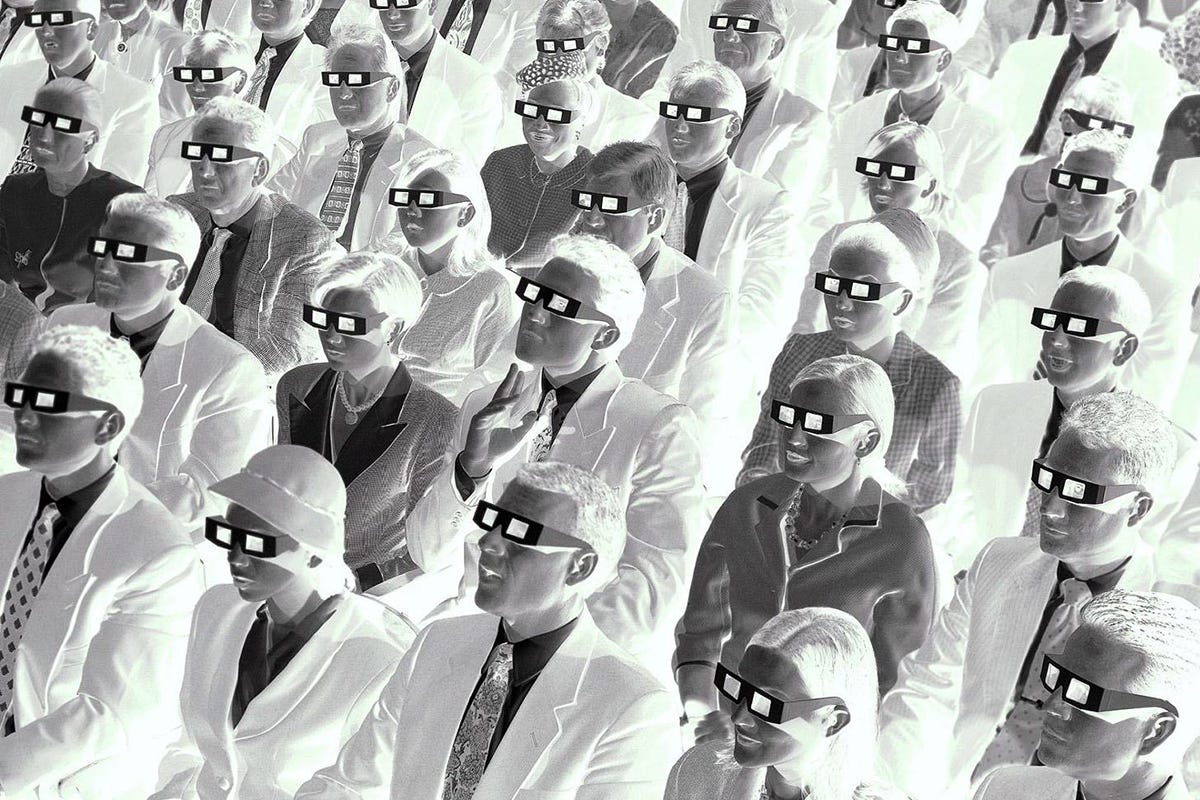

Returning to the question of authenticity, what concepts like trends and virality illustrate to me is the importance of parasocial relationships on our understanding of The Society of the Spectacle.

In his 1967 book, French philosopher and critical theorist Guy Debord outlined a critique of contemporary consumer culture and commodity fetishism, where capitalist relations between commodities have supplanted relations between people. “The spectacle is not a collection of images,” Debord writes, “rather, it is a social relation among people, mediated by images.”

Considering the book’s origins in the late 60s, this spectacle of mediated images has only become more pronounced and pernicious through the advancement of mass media, popular culture, and the digital hyperreality of online communication. For Debord, the spectacle reoriented society around having rather than living, encouraging the consumption of representations of the real rather than preferencing physical interactions in the material world.

In “Negation and Consumption within Culture,” Debord’s spectacle necessitates a culture that continually re-appropriates itself, copying and repackaging old ideas, where a focus on “having” and “appearing” inevitably raises questions of authenticity:

“Ideas improve. The meaning of words participates in the improvement. Plagiarism is necessary. Progress implies it. It embraces an author's phrase, makes use of his expressions, erases a false idea, and replaces it with the right idea.”

For anyone who has seen a Disney or Marvel film in the last decade, this phenomenon will be all-too-familiar. However, I think the connection here between Debord's spectacle and our current state of affairs, is how platforms like TikTok and Twitter are nothing but mediated images and reappropriated representations.

When Halsey makes a video about their label drama, what fans see and interact with isn’t Halsey-as-subject, it’s Halsey-as-image; it’s their mediated persona, their public face. And, in turn, the ideological buy-in of social media becomes a normalised and wilful form of cognitive dissonance: knowing that the online avatar is digital artifice but choosing to engage with it as the real.

In a blog post for Verso Books from 2021, Eric-John Russelladvocates for reaffirming Debord’s spectacle as a tool to evaluate and critique our algorithmic modern world:

“Data-driven algorithms sell to the highest bidder while operating as a requirement for online communication. The demand for pitiless clarity is a demand for an honest business transaction…. Indeed we are currently living in a moment when formulations such as ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’ circulate freely within popular vernacular. It is a situation in which every fragment of conclusive reporting is almost immediately refuted before the day’s end, only to be replaced by even greater and ephemeral certainties.”

Whether it’s solving the murder of Gabby Petito, outing ‘couch guy’ as a liar and a cheater, or vigorously dissecting the very public defamation trial between two abusive celebrity partners, TikTok serves up edited video snippets of mediated life as the real thing, perfectly curated to individual taste, ready for mass consumption and endless reappropriation, with each passing trend more ephemeral than the last.

Even more concerning, at least for me anyway, is how the platform as a virality engine actively encourages this kind of parasocial behaviour, where mediated interactions experienced by an audience in their encounters with performers in mass media take on personal psychological characteristics.

As the late Mark Fisher said in Capitalist Realism (2009): “All that is solid melts into PR.” Or, better yet, just listen to Halsey: “Everything is marketing.”

This is the state of our digital cogito: I Fetishize, Therefore I Am.